Anarchy in the UK and the Anger of Youth: Punk, Post-Punk and Politics

Nick and Tom Pottrill expand on the complex relationship between punk and the politics of the late 70s and early 80s

‘’Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?’’ (John Lydon, 1978)

Punk’s epitaph perhaps? Famous last words, seethed by ‘Johnny Rotten’ as he signed off on the Sex Pistols’ final gig in 1978 and bid farewell to Anarchy in the UK. Perhaps how the ‘Thatcher Generation’ came to feel… or even how the 1978 generation felt…

Politically, the late 70s saw Britain in the ‘dole-drums’ - a sense of national decline fanned the flames of social unrest towards politicians of all stripes. Indignation coursed through British society from the Winter of Discontent in 1978 through to the riots during Thatcher’s first term in office, but the punk and post-punk music which the younger generations listened to represented an elemental rage that transcended politics.

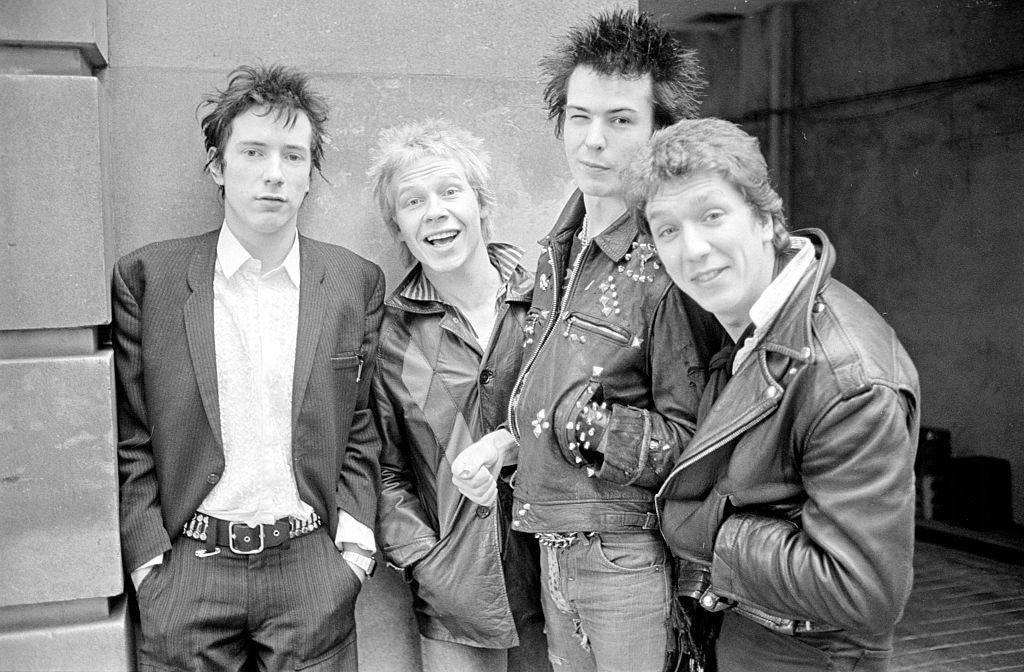

Punk rockers certainly emerged from and reflected a bleak socio-political backdrop, but many punks would eschew all politics, with the Sex Pistols proclaiming a wholly anti-political and anti-social message in ‘anarchy’ for the UK. Many punk lyrics don’t seem all that interested in anarchy either, save for the flag-bearers of anarchy, Crass. To complicate matters further, Crass didn’t even see themselves as ‘punk’, declaring ‘punk is dead’, as it had by 1978 become a fashion statement, rather than any coherent set of ideals. Ironically, the noise they made continued in the vein of punk, at least in Crass’ first flush of youth.

In any event, Lydon’s words and the time at which they were uttered marked – in my mind – a crossover between the eras of ’punk’ and ‘post-punk’ music. It was also the point at which Lydon shed his punk skin and emerged into the post-punk sunlight with Public Image Limited, one of the prime movers in the post-punk era. Remember, however, that the roots of post-punk – as with most genres - lay way before the era itself, as did the roots of punk, despite all of the ‘year-zero’ grandstanding surrounding the year 1976. These roots will be covered in future podcasts…

If punk and post-punk music wasn’t avowedly political and the more political bands within punk cautious to call themselves punk because of punk rockers’ tendency to window-dress, then what did unite this murder of musicians? Anger and disaffection in their purest form, reflected in music which was crude, unpretentious and cathartic. The genre provided a vector for these emotions and more pointed, more political protest.

Post-punk bands with a political axe to grind stuck to issues that were not explicitly ‘party political’, but nonetheless were considered left-wing at the time. Issues such as race, gender, homosexuality or the rights of non-human animals were common. Basement 5, The Slits, Tom Robinson and Robert Wyatt all spring to mind. Other post-punk bands, such as Gang of Four and Scritti Politti, chose a more “academic” approach to their lyrical content, masking their left-wing beliefs in complex lyricism. Take Gang of Four’s tacit deconstruction of early-stage Thatcherite ‘aspirationalism’ in their track ‘Paralysed’ as a prime example.

That said, the major issue uniting both those still relentlessly ploughing the punk furrow and the bands that flourished in the post-punk era was The Falklands War. By the time Britain went to war with Argentina, there was already a growing anti-nuclear and anti-war movement. The CND badge was commonly worn by large swathes of the left and many of the anarchist punk bands of the early post-punk era. Thatcher’s apparent pact with Ronald Reagan to proliferate the nuclear arms race (all in the name of peace) galvanised the peace movement. The Falklands War was therefore a red rag to this particular bull. Naturally, Crass had much to say about it, with some of their records even being referred to in the House of Commons as “unpatriotic”. But perhaps the best anti-Falklands songs were those that were less in your face’ such as Robert Wyatt’s ‘Shipbuilding’. Others may not have been about the Falklands at all. Step forward (no pun intended) The Fall with ‘Marquis Cha Cha’.

So, Britain ‘won’ the war, regained the Falklands and the country did not become nuclear free. Thatcher stayed on for another term, her poor poll ratings of the early 80s overturned by the “glory of the slaughter” (to paraphrase Dennis Healy slightly).

Where next? Well, The Mighty Wah’s 1984 song ‘Come Back (Story of the Reds)’ somehow presaged the Red Wedge movement of the mid 80s, though it was not written as a rallying cry to the labour movement per se. But that’s a whole different story.

Both the punk and post punk eras – which really lasted not much further than 1983 (1984 would be pushing it a bit) produced some fantastic sounds. Most of the songs were apolitical or their lyrics too obtuse to deduce any clear political stance. For the songs that were political, the ‘’issue-based’’ nature of many of the lyrics advanced beliefs once seen as the preserve of the ’loony left’, by both the Thatcher government (and, dare I say, even by many in Her Majesty’s opposition at the time).

Today, anti-racist and anti-sexist beliefs, thankfully, are mainstream in much of British society, millions marched for peace in Iraq in 2003 and Palestine from 2023, and equality and diversity training is now a standard feature of the workplace. Yet the threat of an older, nastier and more reactionary anger looms ever larger in sky-blue.

It may be time to sing those songs again…or maybe even write some new ones.

Our next episode will be released this Sunday 15th June, on the FARSANG Soundcloud. It is with great pleasure that Tom’s parents, Rachel and Nick, join us for the episode! Expect expert insights, funny (and sometimes hazy) anecdotes and a carefully compiled tracklist that captures the essence of the era in which they cut their (young) political teeth.