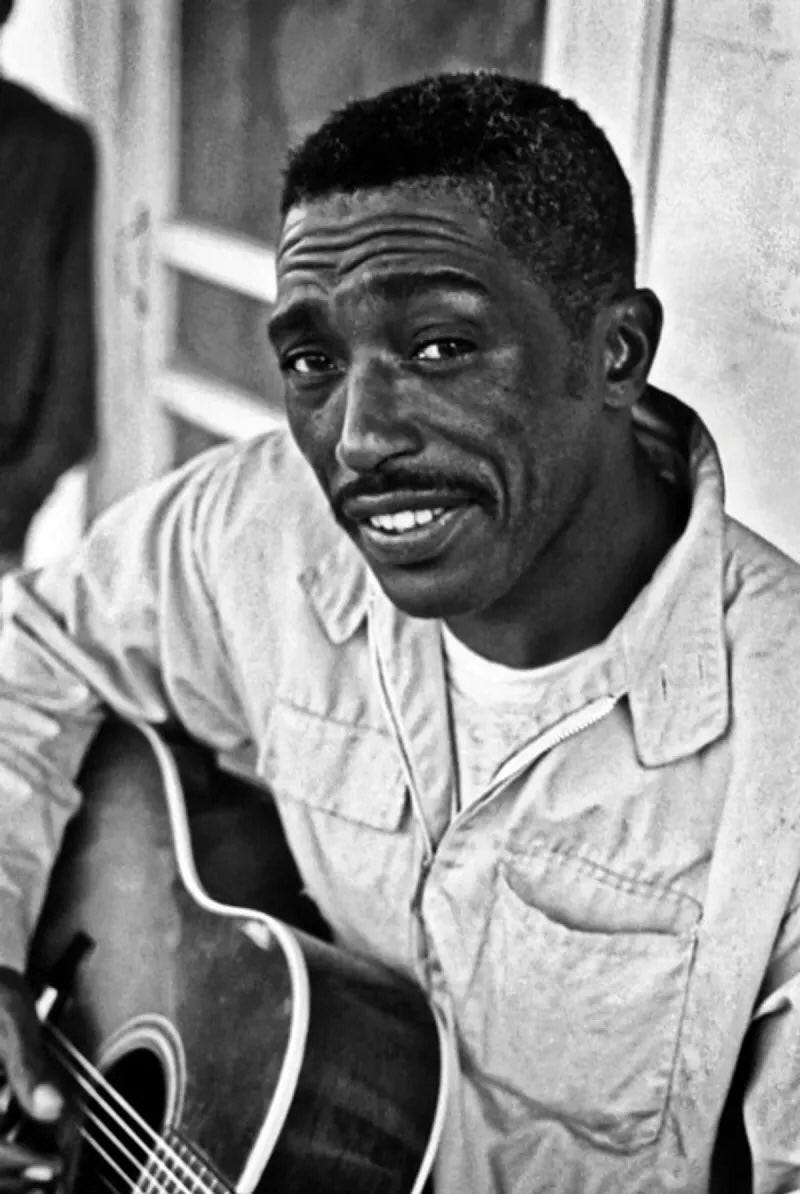

Farsang Profiles: R.L Burnside

‘However, terror did not forge a man who was perpetually on the run, but one who lived alongside it, as only a true bluesman would.’

‘The Blues’ are tough to define. The origin stories are steeped in legend: Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil at a Clarksdale crossroads and crackling recordings of Charley Patton. Reginald D. Hunter, driving through the Delta in a Red Cadillac, observes: ‘Black people just transcribed the blues… white people invented the blues’. Hunter says this with a wry smile, but there is no eluding the harrowing racial backdrop of Mississippi. Blues accompanied the trauma of daily life for African Americans in the US’ poorest state, holding a mirror up to it. For the Rolling Stone columnist Greil Marcus, blues, unlike gospel, ‘was not a music of transcendence… Blues made the terrors of the world easier to endure, but Blues also made those terrors more real’.

If the Blues eludes a clear definition, then it may well have been personified by R.L. Burnside, who passed away in 2005.

R.L. Burnside knew terror well. As a young man in the 1940’s, he left his home in Mississippi’s Hill Country to seek work, first in the steel mills of Memphis, before heading north to join some of his family in Chicago. Two uncles, two brothers and his father were shot dead within a year. Burnside sighs in ‘R.L.’s Story’, from his album Wish I was in Heaven Sitting Down: Yeah… I’m glad I made it out, man’. However, terror did not forge a man who was perpetually on the run, but one who lived alongside it, as only a true bluesman would.

Burnside returned to the Hill Country in around 1951. Later on in the decade, he was convicted of shooting dead a local troublemaker. When the judge questioned his intent to kill, Burnside replied: ‘It was between him and the Lord, him dyin’. I just shot that sonofabitch in the head’.

The few years which Burnside spent in Chicago scarred him, but they were a vital finishing school for his Blues, first imparted by his neighbour Mississippi Fred McDowell. Burnside would regularly visit Maxwell Street to watch his cousin-in-law, Muddy Waters, and another behemoth of Chicago Blues, Howlin’ Wolf, play. Muddy Waters no doubt influenced Burnside’s slide-guitar technique, and one wouldn’t be mistaken for detecting shades of Howlin’ Wolf in Burnside’s notes. The respect which Burnside pays to other greats of the genre, in covers of their songs and his own style, sets him as something of an outlier within Hill Country Blues.

Chicago provided an opportunity for Burnside to refine himself as a bluesman. Yet he was Hill Country to the core, having grown up among the fife-and-drum ‘picnics’ of the area. The fife-and-drum picnic, now all-but extinct in the South, fuses the polyrhythms and spiritual dances of African slaves with martial instruments brought over by Ulster Scots settlers, forming a bridge between the music of the Delta and Southern Appalachia. An infectious fife-and-drum derived rhythm features in classics such as ‘Jumper on the Line’ from Mississippi Hill Country Blues (1984). This and a distinctive ‘groove’ separates the Blues of the Hill Country from the Delta and Chicago varieties.

After returning to Como, Mississippi in 1959, Burnside remained in the Hill Country, working as a sharecropper, fisherman and manual labourer. For much of his life, music provided him with next to no income and his genius was largely confined to the juke joints, ramshackle taverns that were usually converted from abandoned out-buildings. These were once bastions of Black-belt Mississippi; places where people could drink off the day’s travails, find love and ease loss. Some remain in the Delta and Hill Country to this day. ‘Rule’ was a regular fixture at David ‘Junior’ Kimbrough’s in Chulahoma, Mississippi. Kimbrough’s joint had become a firetrap by the late nineties, and had burned down by the turn of the millennium. With it died the raw, heaving Blues of Kimbrough, Burnside and Bruce Watson, and the fire pit at its centre.

Burnside’s blues would likely have continued in obscurity had it not been for Fat Possum records, who signed him in the early 90’s. Founded in 1992 in Oxford, Mississippi by Matt Johnson and Pete Redvers-Lee, the label provided an outlet for Hill Country bluesmen when they were wary of exploitation by larger record labels. In some respects, the two were a good fit. Fat Possum has gone bankrupt several times since it was founded. Likewise, Burnside’s newfound success did not translate to financial security, as the number dependent on him grew almost in proportion to every album that he recorded and accolade that he won.

Despite their financial difficulties, Fat Possum brought national and international recognition to the bluesmen of the Hill Country. Kimbrough, Watson and Burnside developed a cult following, touring and headlining festivals, after years of juke-joint and backyard performances in kudzu-shrouded anonymity. Kimbrough’s first album was given a five-star review by Rolling Stone, and Burnside toured with the Beastie Boys. This explosion of activity is reflected in Burnside’s heavy output through the 90’s, a mix of rejigged classics and label-led experimentation. Burnside found these fusions of Hill Country Blues and Electronica wholly puzzling: ‘I thought it was coming out just like we did it, you know. And then it come out remixed. I didn't like it. But it's selling’.

Burnside’s 1994 album Too Bad Jim errs more towards pure Hill Country Blues and is perhaps his best work. It features songs which had been in Burnside’s repertoire for decades. Riveting chords and a groove inherited from the fife-and-drum populate a work in which Burnside lays himself bare. He makes tacit references to the trauma of his time in Chicago, fleeing the ‘chilly wind’ of the North in Goin’ Down South, repeated almost as an incantation. Death Bell Blues, true to genre, confronts the terrors of the world head-on, each chord ringing out like the knell of a backcountry Church.

Too Bad Jim represents the apogee of Burnside’s musical output, which we could dwell on for a while longer. But I’ll leave you with a final note on the man. Even as his health faded, Burnside’s penchant for hard-living did not. Johnson and Redvers-Lee recall how Rule came down to Oxford, Mississippi having suffered an engeoplasm. A lifelong commitment to Bourbon and cigars had left three arteries clogged. Undeterred, Burnside headed for a Ladyluck casino in nearby Tunica, requesting a small advance to ‘push his luck’.