Fes in Photos: Between History & Modernity

Rowan Glass and his camera take us through Fes' multi-various qualities, through history and the present-day.

In October 2023, I spent a week in Fes, Morocco: the “Athens of Africa,” one of the cultural and spiritual capitals of North Africa, and a place dense with history. Founded by the Idrisid dynasty in 789, it was here that one of the first universities in the Islamic world, the University of al-Qarawiyyin, was established in 857–859, rising to prominence as one of the centers of the Islamic Golden Age. For more than a thousand years, Fes has remained one of the premiere cities of Morocco, North Africa, and the wider Islamic world.

I arrived in Fes to attend the On the Road photography workshop with Nikos Economopoulos, a Greek photographer signed with Magnum Photos and known for his lifelong documentary work in the Balkans. For me—easily the least experienced photographer in our cohort of eight students—the goal was to hone my photographic eye, improve my shooting technique and editing skills, and end the program with a portfolio I could be proud of. I also wanted to move away from the merely documentary or photojournalistic and into the realm of the poetic—for Nikos, the ultimate ideal of photography. I’ll leave it to the viewer to judge whether I succeeded.

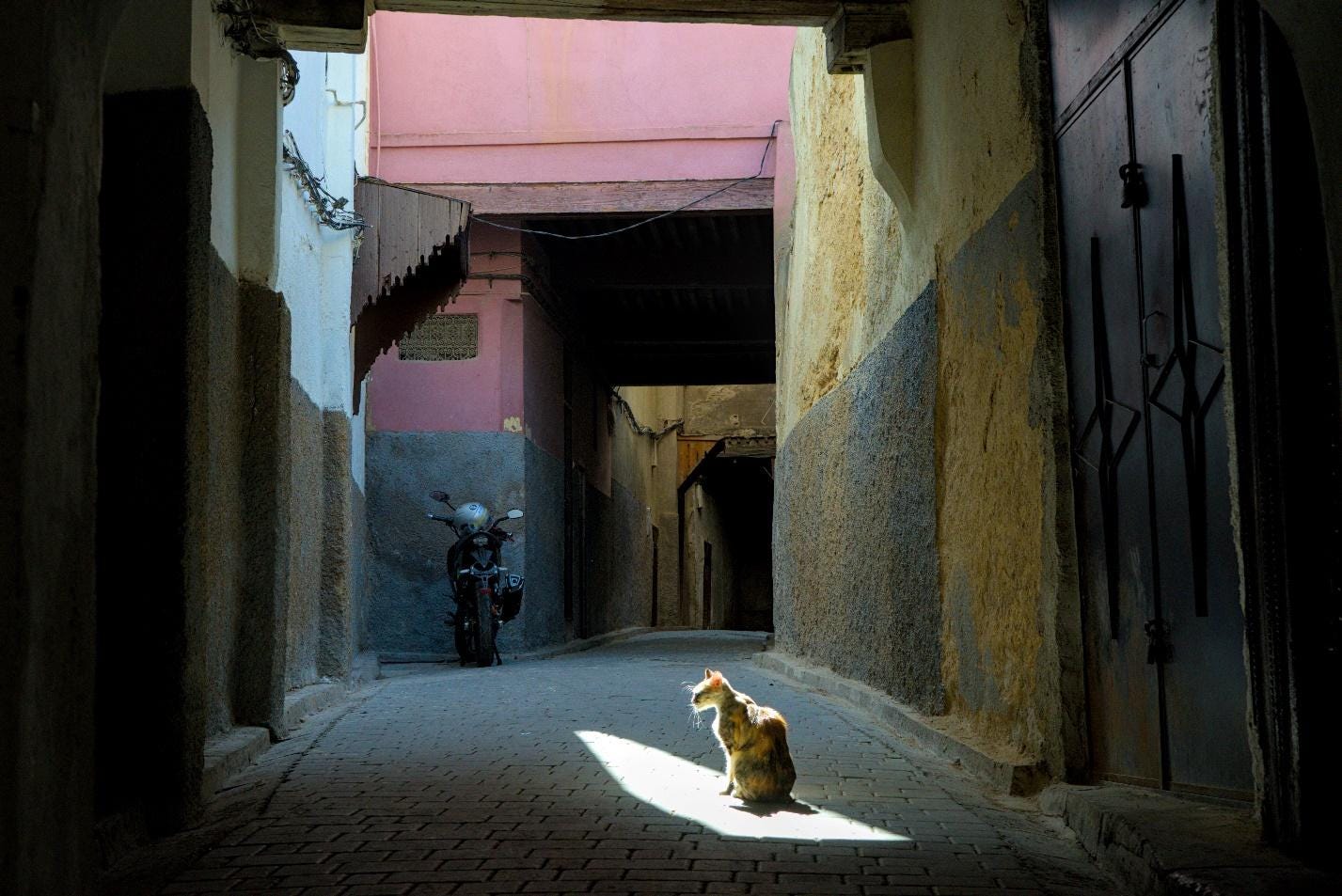

You could be forgiven if you stick only to the dense and teeming chaos that makes up the medina of Fes, one of the largest, oldest, and best preserved in the Arab world. It’s there you’ll find all the exotic sights and smells one associates with the romantic—if a little Orientalist—image of the North African marketplace. All the classic archetypes are there: the tireless merchant willing to follow you down ten streets to make a sale; cats, the favourite animal of the Arab world, lounging everywhere you look (when not scrounging for scraps in the gutter); piles of fragrant spices and plump dates neatly arranged before market stalls draped in the geometric shadows cast by the woodcut rafters of the bazaar’s vaulted ceiling…

But I didn’t want to take the same photos every tourist takes. I felt it would be an error to linger in the medina—there’s more to Fes than that, and one finds different textures in the city’s urban landscape the further one strays from its touristic centre. My photos try to capture some of those shades of difference in the various districts I wandered and the encounters I shared in them.

Here in the Mellah, two carpet salesmen try to land a sale. The Mellah is the historic Jewish quarter of Fes. Morocco was once home to the largest and oldest Jewish popuations in the Arab world, though most have left for Israel. Historically, Moroccan Jews were split between two populations: the older Amazigh Jews, who spoke Berber and Arabic dialects with borrowings from Hebrew; and the Sephardim, who came from Spain and Portugal following their expulsion from Iberia in the 1490s. Though there are now only some 2,500 Jews left in Morocco, the influence of their long history in the country remains. Morocco is one of few Arab nations to have maintained relatively cordial relations with Israel, where Moroccan Jews constitute a sizeable community. Finally won over by their tenacious haggling, I left the merchants’ shop with an antique Jewish carpet in hand.

With a median age of less than 30, Morocco is a relatively young country. It’s not uncommon for groups of children to approach foreigners on the street to beg for money. Sometimes it takes an emphatic no in French, English, or Arabic for them to stop. This boy pulled a classic trick on me, offering to take me somewhere interesting for photos with the unstated expectation of a few dollars in coins. It turned out to be an abandoned, overgrown courtyard which wasn’t worth the ten-minute trip down the meandering and intrinsically more interesting alleyways of the Fes medina. But in the end, I got this photo and he got his coin.

Leaving the medina, I pass through the gates of the ancient city and wander uphill into the commercial district of Andalou, where grimy concrete replaces the storied brickwork of the walled city. A florist gestures an angry reply to the penetrating stare of my camera, and I wonder whether I’ve wronged him by creating this unequal relation of power with a snap of the shutter, immortalising his defiance. Nikos tells me that’s a question to trouble the anthropologist but not the photographer, whose duty is to the image and not its subject. In any case, this man’s reaction was not unique; the middle finger became a familiar gesture during my week in the city, suggesting locals’ occasional hostility to tourists on the prowl for the right shot.

Above and to the north of the medina stand the Marinid Tombs, the remnant of a necropolis built under the auspices of the Marinid Sultanate long gone to ruin. The Marinids were an Amazigh dynasty of orthodox Sunni successors to the radical Almohads, extremists known for putting to the sword Jews and Christians who refused conversion to their heterodox vision of Islam. Being a popular lookout point for tourists, the tombs attract peddlers whose livelihoods depend on roping visitors into buying their wares. But when the sale is made and the tourists go, an ethereal air asserts itself here, and the salesman is left alone under the afternoon sun facing a horizon that merges imperceptibly with the limpid sky above.

Now, looking down at the medina from the northern hills, one perceives how those ancient walls divide the bustling souk from the whitewashed tombs of the Bab Guissa cemetery, spaces of life and death in neat juxtaposition. Centuries of habitation, generations of families come and gone, yet still they find space for the newly dead here, for someone is always digging a fresh grave.

It’s something of a tired trope to lament the status of the poor veiled women of the Arab world, oppressed by their religion and dominated by their men. Whatever truth there is there, there’s often also more than a tinge of Orientalism or Western self-righteousness behind such representations, as if “we” have done so much better. As Frantz Fanon wrote of the veil in the context of Algeria’s war of liberation from France: “The woman who sees without being seen frustrates the colonizer.”

In any case, the place of women here is as dynamic and variable as anywhere—rigid sometimes, certainly, but always also open to negotiation and challenge. As for the veil, its use in Morocco is considered a personal religious choice, and in urban areas, it’s not uncommon to see women in hijab, niqāb, and unveiled alike walking along the same street—a more cosmopolitan atmosphere than many outsiders might assume.

West of the medina is the Royal Palace of Fes, one of numerous residences reserved for the royal family of Morocco. Despite the city’s arid climate, the grounds of the palace are always kept green in the expectation that the king might arrive at any time. Mohammed VI, the king since 1999, is the richest monarch in Africa and one of the richest in the world—this in a country facing entrenched wealth divides and widespread poverty. In response to the Arab Spring, the 2011 Moroccan constitutional referendum nominally weakened the powers of the king, defining the country as a constitutional monarchy. However, the king remains a powerful figure, and it is a criminal offence to publicly criticise him. Even so, his popularity remains relatively high.

Walking further west from the Royal Palace, one comes to the Ville Nouvelle, the “New Town” of Fes. Though rarely visited by tourists, this modern city constitutes the bulk of Fes today. Here, free from the crowds and cramped chaos of the medina, life goes on much as in any urb of modern Morocco.

Back in the medina, this palm catches my eye. Was it planted? Or did it grow here of its own accord, and no one bothered to remove it? Is it one of those entities whose absence is never felt until its presence is known? New life takes root here in the residue of history.

My sojourn through Fes comes full circle, ending in the alleyway where my riad, a type of traditional Moroccan courtyard house, is located. Having peered in these snapshots into other lives and other times, my own time here has come to an end. Fes as I knew it lives now only in my memory and these photos.