FARSANG Interviews: Sharghzadeh

FARSANG spoke to our good friend Muhammad Ali Mojaradi, aka Sharghzadeh, editor and founder of Persian Poetics.

Find Muhammad on his social media platforms:

Join his Persian Poetry classes and reading groups on his website:

FJ: Tell us a bit about yourself. How did your upbringing influence the path you’re now on?

MAM: My name is Muhammad Ali Mojaradi. I am 24… I think… I lose track nowadays!

I was born near Detroit, Michigan. I was raised between there and Tehran, Iran. I spent around 14 of my first 18 years in Detroit. I’d visit Iran every other year and I lived there for a year during high school. I had a standard immigrant upbringing, but for the fact that I didn’t grow up in an immigrant-heavy neighbourhood, as others did; in this case you might be poor but you’re with your people. I grew up isolated from Middle Eastern and Muslim culture apart from trips to the mosque and restaurants at the weekend. My neighbourhood was about half White American and half Middle Eastern Christians, but they were the affluent business class, so they tried their best to be American. I think that gave me a good sense of American culture. I have a bit of both, you could say.

When I was 16 I moved to Iran alone. I was having a few issues at school. I’ve always had issues with authority - when applied arbitrarily, that is - and I had just had enough of American schooling. My parents were done dealing with my school problems. Sometimes parents send their kid back to their home country to get ‘straightened out,’ but it wasn’t like that for me. They didn't want me to go, I just wanted to go back to Iran. I didn’t let it go for six months; the second half of 10th grade. I kept saying ‘I need to go, I need to go’ and everyone was like ‘you’re crazy, what are you going to do?’. I finally persuaded them to let me go, but they only wanted me to go for the summer. They thought that I would eventually come back, because they figured Iran was too much for me to handle. Later I realised that they had told people to not challenge me and tell me I couldn’t last. Theylast They thought if I felt too much resistance I would go for the year and stay no matter what, just to prove myself.

I was finishing highschool in Iran, but there was no chance I could go to Iranian University with my shoddy diaspora Persian, even after a year of living and studying there. So I came back to the United States for university. I ended up studying economics. I wasn’t that interested but as it goes in immigrant households: “Why did we bother moving here to America if you’re going to get a pointless degree?”

One day I was walking by an auditorium on campus, the door cracked open and I happened to catch a glimpse. I saw ‘Iran’ written on the board, so I walked inside, having only been back for a year at that point. It was in my second year of College - University to you Brits - and I saw that there was a lecture on Iranians. At the end of the speech the Professor, Camron Amin, said ‘Hey, by the way, we need a translator who knows colloquial Persian’ - it was an ethnography project, interviewing Iranian-Americans - so I introduced myself and got the job. I thought ‘I want a job, I could do that.’ I was doing construction at that time, which I hated. It was gruelling work; I would work all day, and come home dirty and injured for low pay. So I got a job with him, and he became my mentor. One day he said, ‘You really should be majoring in Middle Eastern Studies, not Economics.” I’m very indebted to him for his guidance. He took me to a conference using a university grant and eventually convinced me to do a minor in Middle Eastern Studies. That’s what got me on the path that would eventually take me to Jordan.

In Jordan I was studying Arabic. I was finally a fully-fledged adult, financially independent and alone in a new country. I had moments where I re-considered and doubted what I was doing. Those feelings were intensified when the Coronavirus pandemic began. I returned to the United States and had nothing to do. I was at home and my parents were saying ‘Your year abroad is done, it’s time to get on with your life!’ I didn’t want to get a job with my economics degree, but I felt my hand was forced. What else was I going to do? But then lo and behold, my internet project (which was only a hobby at the time) went viral, thanks to a Twitter thread that struck a nerve with hangry Muslims during Ramadan. It’s been over a year and a half, and since then I have been independently studying, translating, and teaching Persian poetry full time. That’s where I’m at right now, sorry if I rambled!

FJ: Where do you call home? What does home mean to you?

MAM: I really don’t know. I was talking about this with some friends the other day. We’re all diaspora Muslims who feel stuck between where we’re from and where we grew up. Home could be where you feel at home, or perhaps where you ‘plant your roots’.

It’s hard. Sometimes I go to Iran for a year and feel like that’s home, but I feel the same way when I’m in America and see my friends. Our sense of home being split between two places is really a modern problem. In the past when you went to America, there was no ‘going back’ to Europe. Home was now in America; you couldn’t just sail back. Rumi, for example, left Khurasan and lived in Konya, with no sense of returning to his hometown.

When I was in Jordan, Amman started to feel like home a little bit. It may have stayed that way had it not been for the pandemic, who knows.

FJ: What effect can the transition from a more community-based to a more individualist society have on the mental health of people who migrate?

MAM: I think the discourse surrounding this lacks nuance. Far-right groups always cite immigrant crime statistics to stoke xenophobia, implying that we are inherently violent or criminal. But these crimes are mostly western phenomenon. When people are transplanted to a society with a weaker social fabric, combined with poverty, isolation, and other issues like PTSD, it isn’t surprising some of them will commit crimes. When you move from a collectivist society to an individualist one, the bonds that we are used to dissipate and you don’t know what to do about it. Those of us who’ve grown up in an individualistic society know how to deal with the isolation and lack of family support. But for some new arrivals it can be too much.

Many who go to the west break down for various reasons. Oftentimes, the men will migrate alone and eventually marry in their home countries, because they lack the language or cultural familiarity to marry in their new home. Then they take their spouse to the new country, and the spouse will suffer there as well. It’s often the first time they are far from their family, they have to adjust to married life, and on top of that they have to learn a new language and culture. This becomes especially difficult when they have kids, because they’re used to a support network of relatives and friends who would help them care for their kids in the early stages. There’s so much stress, and we don’t realise it because we were raised in the West, but when you see people fall apart here after coming from collectivist societies you realise that there is something fundamentally wrong with our individualist lifestyle in the West.

Before my last year at UofM I got a message from a stranger. He said he was leaving Iran to study at our university, but could no longer afford an apartment because of the Rial’s collapsing value. My roommates and I gave him a makeshift space in the corner of our living room. Over the years, I helped him adjust to life in America. We lived near a poor area, on the bus we would see homeless people and drug addicts. We saw people lingering in empty parking lots, even in winter. He’d say: “Muhammad why are there so many people with no place to go? What happened to them? Are they refugees?” I said: “No, they’re from here.’ And he’d say: “What’s wrong with them? Don’t they have a cousin or someone who could take them in?” I explained that they do have family, but they are likely not welcome to stay with them because of their drug or mental health problems. He was aghast that someone could have nowhere to go. I had always taken homelessness for granted, but he made me realise how evil it is that we have a society where families let their relatives remain homeless, where people are discarded onto the street like trash.

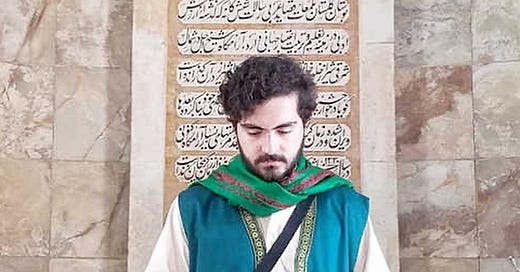

FJ: Those of us that follow your work and know you personally know that you’re very passionate about traditional clothing. Why is it so important for you, and where did this passion come from?

MAM: Before I liked traditional clothing, I despised suits. There was always something I didn’t like about them. The belt was annoying, the collar was tight and the tie always had to be adjusted. I hated that I was often forced to wear suits.

At university I started to see Arabs straight from their home countries wearing Arab garb on some days. Then I was elected into the student government and I was required to wear formal attire. I didn’t want to wear a suit anymore, so I asked if I could wear Muslim formal attire. They said it was alright as long as it was formal, so I went to an Muslim neighbourhood in Detroit and bought a long dress. It attracted some comments when I turned up to the first Student Government meeting. People thought I was wearing a dress as a joke or as a costume. It got me to think, why is there a suit hegemony? Why do people assume our native clothes are a costume, or a joke? Jean, you guys [Italians] started it. How did this become the international standard? That’s not fair. Why does one culture get to set the standards for what’s formal?

This ignited a passion for traditional clothing. I started to buy clothes on trips to Iran, and the resistance I encountered only made me more passionate. Once I asked a girl out and she matter-of-factly told me: “Please wear normal clothing. I can’t deal with the clothes!”. I thought wait a minute, you’re from an Arab country! Doesn’t your Dad dress like this?!” There was this feedback loop where the pushback made me more committed to traditional clothing. There was no symbolic moment where I burned all my Western clothes, I stopped buying them and slowly they were replaced with traditional clothes. It unintentionally became part of my persona; people would recognise me as ‘that guy who wears Middle Eastern clothing’ around campus. I didn’t mean for it to happen, and it’s not for attention. I actually dislike the attention I often receive, it’s mostly negative.

Over time I fell in love with the clothes themselves. I now love finding tailors in the bazaar alleys of Tehran and Amman or visiting cities and finding their traditional clothes.

FJ: For those who don’t speak Persian, could you explain what Sharghzadeh means?

MAM: There’s this Persian book by the socialist thinker Jalāl Al-e Ahmād entitled ‘Gharbzadegi’. Gharb means ‘West’ and zadeh means ‘struck’. The book popularised the term, it was applied to Iranians who had an Eastern inferiority complex with a derogatory connotation.

When I was in Iran, my clothing once caused a heated back and forth with my family. I was accused of dishonouring the family by dressing like a villager, so I said they were all Gharbzadeh. They said fine, you can be Sharghzadeh. So Sharghzadeh - ‘East-struck’ stuck, and I started using it as a social media handle, in a both serious and joking way.

FJ: PersianPoetics has really taken off in the last year or so. Where do you see your project going in the next few years?

MAM: Social media has a limited reach, and this is by design; for Twitter as much as Instagram. They want us creators to pay for exposure, the algorithm is a rigged game. I’ve been thinking about pivoting away from it for some time. Writing books is a possibility, I am working on a few concepts at the moment - that’s how my mind works, I can never concentrate on one all the time. I am currently teaching courses and hope to host some Persian Poetics meetups or perhaps do a series of in-person talks in the future. I’m looking to expand to other languages as well. I want to improve my Arabic and begin translating Arabic poems written by Persian poets. If I had a Sultan funding me I’d hire a small team and start Turkish, Urdu and Arabic equivalents of Persian Poetics. I would make a YouTube channel too. If there was more money so much more could be done.

FJ: Given all the work it takes you to keep up such a popular and well-received project, you must sometimes wonder ‘why am I doing this?’. Why do you do what you do?

MAM: Absolutely. This is especially an issue being a Muslim creator. Sometimes I feel if I was Jewish or Christian I would already have a full-time job. Muslims act like crabs in a bucket. It can take up to two hours for me to translate, verify, edit and write a caption for a post - and sometimes half the comments will be negative.. It’s usually armchair critics pointing out something as petty as a dot or comma missing. On the flipside, I get messages every other day from people who say my page is their favourite. In the past I would ask them to donate a dollar and they would leave me on read, but those same people would be driving a luxury car. There are moments when these things get to me and make me feel like I should just quit. Why bother committing so much time for a culture that doesn’t really care about itself? Why take such a big risk? These are the years where I should have career growth, but I’m spending it doing independent scholarship with very little funding. But ultimately my passion and some recognition helps motivate me.

FJ: On your social media you often give examples of everyday usage of poetry in Iran (something that goes beyond social class/education) - what effect do you think this has on a community? Would the world (particularly the West in this case) be a better place if poetry wasn’t seen as something for elites?

MAM: Poetry expresses our deepest thoughts and softens the hearts of readers. You’re unlikely to meet someone rude, crass and unrefined interested in poetry. When you have poetry ever-present in society, which is the case in Iran, it helps create a rich culture. This culture carries over to the diasporaI. I often see Muslims taking interest in and even quoting English poetry. I remember once I heard an Arab Briton quote a proverb: ‘He that complies against his will / Is of his own opinion still’. This is something Persian and Arabic speakers do. Sadly English speakers seem to be losing their connection to poetry.

Sadly modern people are growing to despise traditional culture. Now and again there is talk about removing greats like Shakespeare, Dante, and Chaucer from university curricula because they are all white men. I don’t care - I’ll happily read them anyway. The goal of creating an equitable society is good, but it would be a shame to throw the baby out with the bath water. These gems of the past are worth saving, even if they go against our modern mores.

There’s so much wisdom to be inherited from our ancestors, whether Muslim or not. As tacky as average Americans find them, I love it when religious Christians quote the Bible in daily speech, you don’t see that much anymore. I find that so beautiful. So many of our modern problems are caused by a lack of meaning and community belonging. That could be remedied with these traditions.

FJ: Do you have a favourite poet/poem? Tell us a bit about what it means for you.

MAM: I feel most connected to Hafez. When I read his poems, it feels like he is confiding in me. Unlike Saʿdi, who is very easy to decipher, Hafez is more ambiguous. You don’t always know exactly what he is saying. Everyone can read him and relate. Religious and secular people, Shiʿa, Sunni, non-Muslims, all feel that he speaks to them.